When you talk to 2 different anatomists or plastic surgeons or dermatologists or anyone who has an affinity to facial anatomy about facial ligaments you will get 8 different opinions on this topic. The reason for this is that facial ligaments are poorly understood.

From an anatomic perspective (and by definition), ligaments in the human body extend from one bone to another bone and connect and stabilize the respective joint that connects these two bones. For example, the cruciate ligaments in the knee are a ligamentous connection between the femur and tibia and control certain movement of the knee joint. They are composed of 90% collagen Type I and 10% collagen Type III.

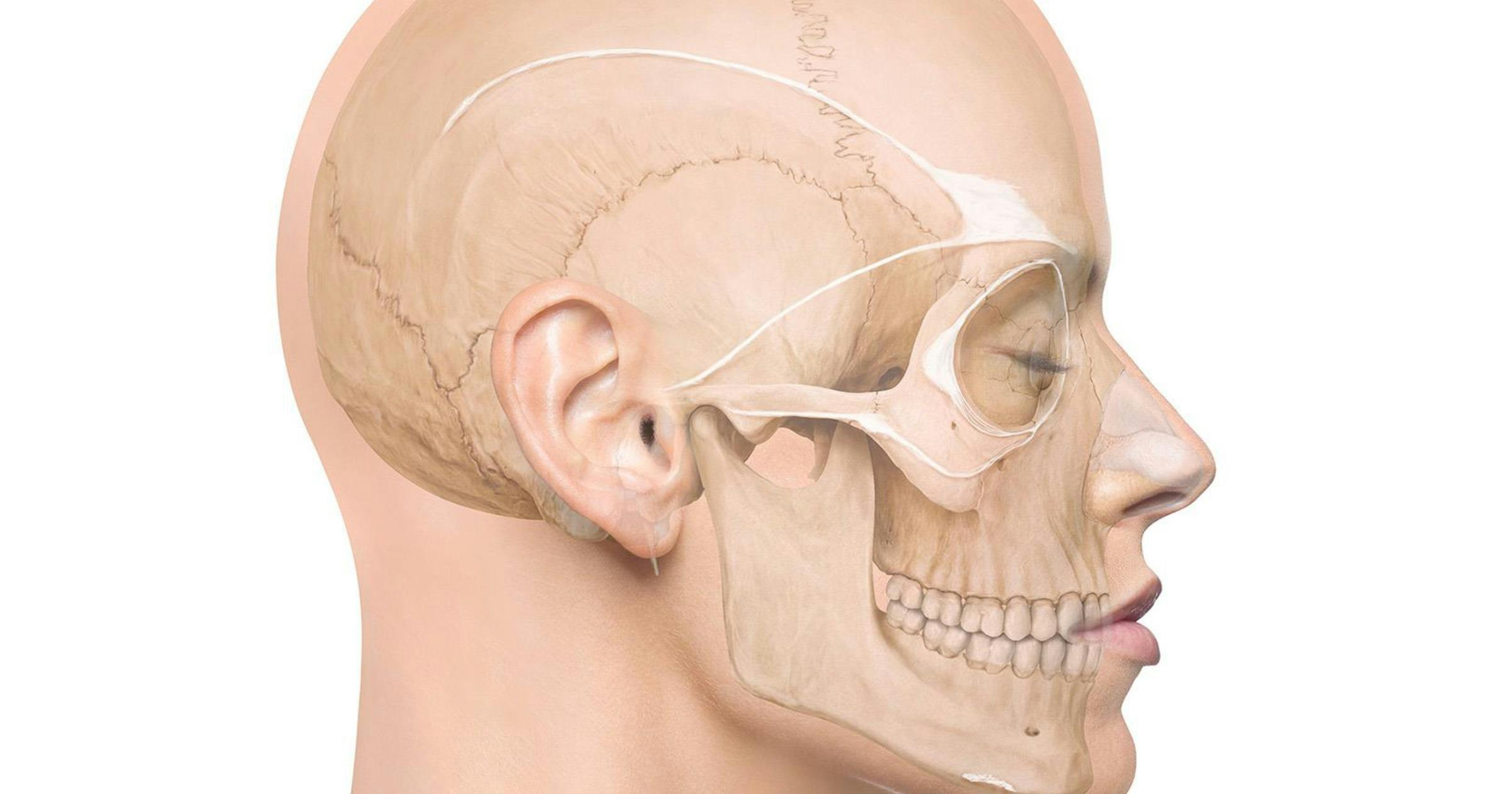

Image credit: Cotofana, S., Wesker, K.H., & Kolster, B.C. (2025). Facial Anatomy: Layer by Layer (1st ed.).

Figure 1: Overview of the most relevant facial ligaments

However, in the human body, we also have tendons. Tendons (by definition) connect a muscle to a bone via a transitional zone made of fibrocartilage which is referred to as enthesis. Approximately 80% of a tendon is made up of collagen Type I which allows for its strength and force-transmitting capability.

An example of a tendon is the hamstring tendon, which allows the muscle of the posterior thigh to connect to the pelvis, or the calcaneal tendon (= Achilles’ tendon), which allows the triceps surae to connect to the calcaneus.

(Figure 2: Detailed image of the zygomatic ligament, when the SMAS is elevated)

Now, when we try to identify and find ligaments in the face, we will realize that no structure in the face actually warrants the name ligament. This is because there are no bones in the face that are connected via a ligament as per the terminology above (if we exclude the temporomandibular joint with its ligament and the mandible with its stabilizing sphenomandibular and stylomandibular ligaments).

But the terms we use for the zygomatic ligament, the orbicularis retaining ligament, the zygomatico-cutaneous ligament, and the mandibular ligament, are not really 100% anatomically correct. Because they connect bone to skin or bone to muscle, the latter should warrant the term orbicularis tendon and not orbicularis retaining ligament.

But we are not here to change the entire terminology of the face which is confusing enough anyways. Instead, let us look at how ligaments truly look like. Those of you who have an ultrasound will realize that fascial ligaments are simply fascial condensations that extend from deeper to more superficial planes.

These ligaments can be compared to studs or buttons which connect multiple fascial planes to each other in one specific spot. They can be found in areas where muscles connect to bone (zygomatic ligament, orbicularis retaining ligament, mandibular ligament) or where fasciae firmly stick to each other and form boundaries.

Such boundaries are the temporal ligamentous adhesion, the supraorbital ligamentous adhesion, the superior and inferior temporal septum, the zygomatic-retaining or the zygomatico-cutaneous ligaments. Previous researchers understood this dilemma and tried to introduce the term true ligaments or false ligaments.

The latter term (false) is applicable when the ligament starts at the bone but does not reach the skin, and instead ends somewhere in other fascial layers (for example the maxillary ligament), whereas the term true ligament is applicable if the ligament spans all the way from bone to skin. Now you can imagine that this terminology caused even more confusion which is why we do not use this classification anymore.

So, what to do?

Here is our 2 cents on this topic:

Join our community for news, offers, and updates on Cotofana Anatomy’s events and resources

Copyright © 2026, Cotofana Anatomy. All rights reserved.