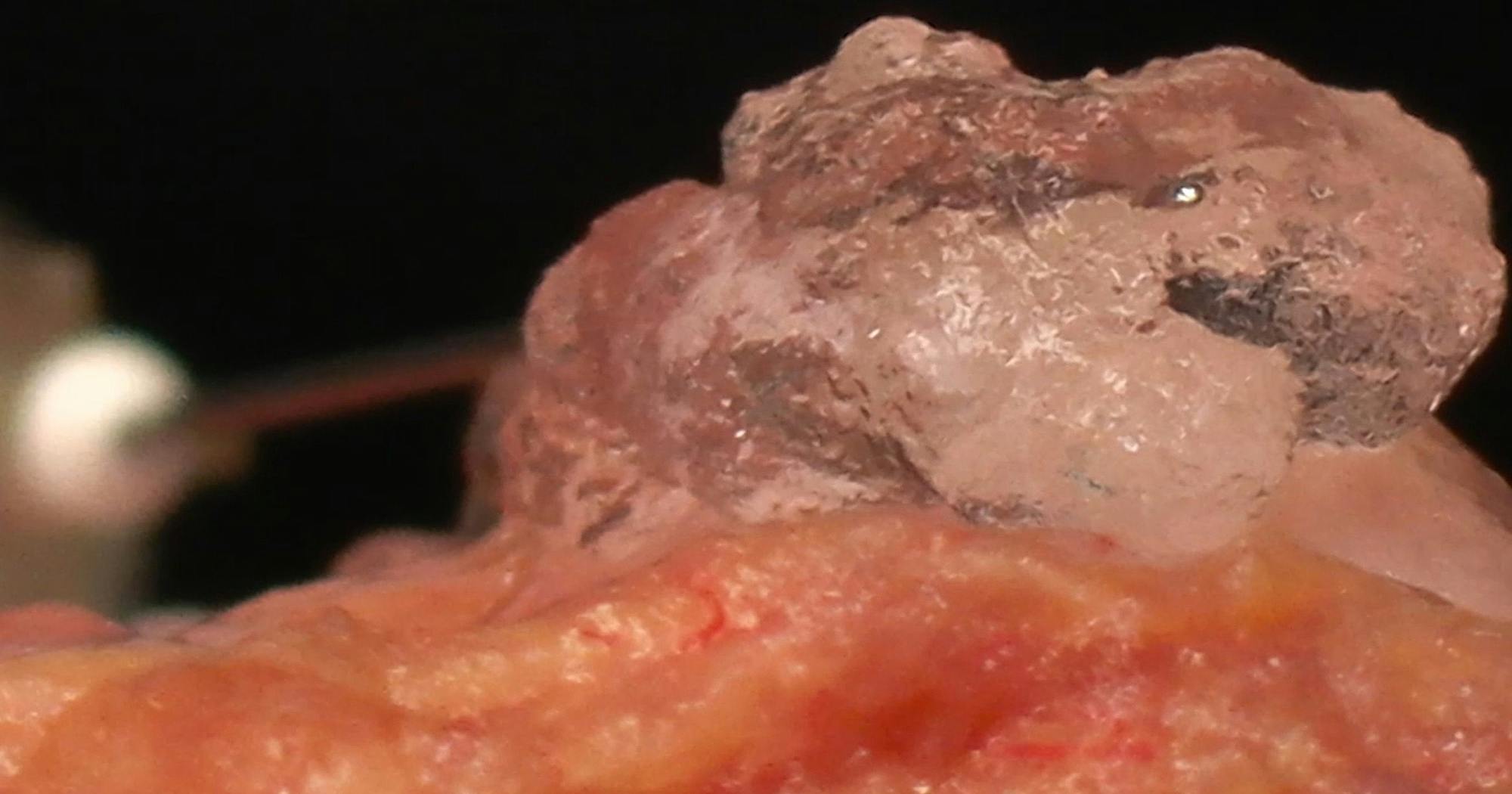

All aesthetic providers have, at some point, worked with hyaluronic acid–based soft-tissue volumizers, also referred to as “fillers” or “HA fillers.” They are widely used to resubstitute lost facial volume during the process of facial aging or to change the facial shape, outline, or bony projection. Depending on the aesthetic needs of the patient and the selected treatment algorithm, a soft or a more robust soft tissue filler is utilized. For instance, the tear trough or the lips are addressed with a softer product, whereas the jawline or the deep temple are addressed with a more robust product.

Pharmaceutical companies offer a wide range of such products and use variables like G-prime, G-double prime, Tan delta, G-complex or other non-tangible differentiators to characterize their HA fillers. What is interesting however, is the fact that these variables are not constant and change during the injection process. Yes, a filler in the syringe has other visco-elastic characteristics than the (same) filler after it passes through the needle/cannula and is injected into the facial soft tissues. However, the greatest change in viscoelastic characteristics occurs when an HA-based soft-tissue filler is subjected to stress. Stress includes pressure, stretch, or movements occurring during various facial expressions. During these motions, a filler changes its visco-elastic characteristic and the above parameters (G-prime, G-double prime, Tan delta, G-complex, etc.) change as well. A previous study has shown that a soft HA filler injected into a high-mobility facial region like the lips, is capable of turning into a hard filler when exposed to high stress.

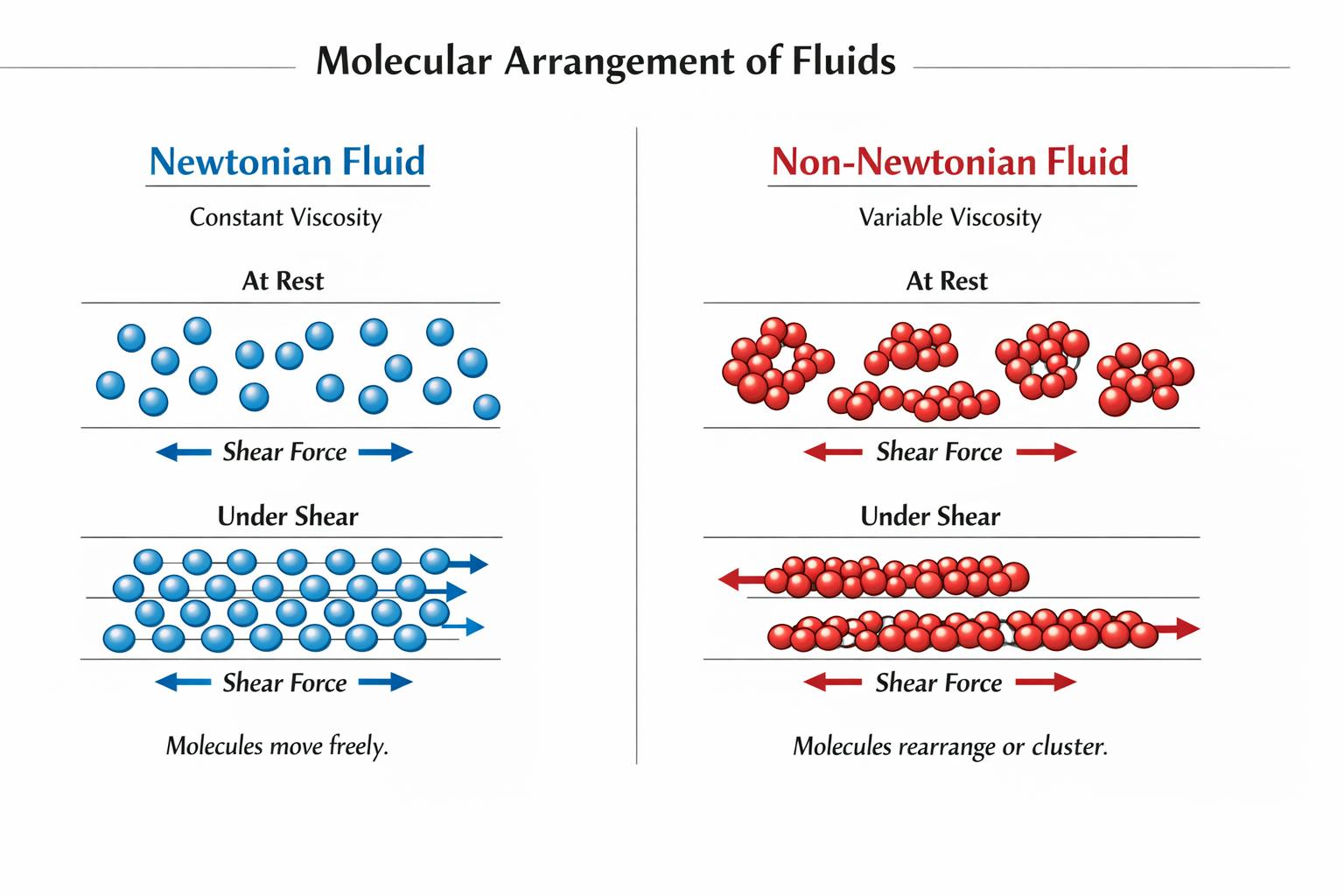

But how is this possible? How can a HA filler or any type of fluid suddenly change its response to stress? Because we all learned from Sir Isaac Newton in his book titled “Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica”, released in 1687, that there is a direct proportional relationship between stress and flow resulting in constant viscosity. Just for clarification: flow is what we measure on the outside, viscosity is the internal property of the substance itself (= external versus internal).

The answer to this is that HA fillers belong to a different group of fluids which are referred to as non-newtonian fluids i.e. fluids that do not follow the laws that Mr. Newton described in the 17th century. These fluids change their viscosity in response to stress. Some become less viscous and are called shear-thinning fluids (like ketchup), whereas others are called shear-thickening (like HA fillers or oobleck).

In non-Newtonian fluids, changes in viscosity under applied stress, and thus their viscoelastic behavior, are influenced by the size, electrical charge, and degree of molecular entanglement of the suspended molecules. Let’s review this in a theoretical experiment: A non-Newtonian fluid needs to pass through a narrow opening at the end of a tube. You push the fluid along the tube and when the opening is close the walls of the tube apply pressure on the fluid. This pressure results in two possible scenarios:

1. The molecules within that fluid align perfectly like elementary school kids on their way to the zoo and the fluid can pass easily through the opening

2. The molecules jam and entangle causing the fluid to not be able to pass easily through the opening similar to a crowd of people lining up in front of a store in the morning of Black Friday.

This same setup can result in a different flow rate of the non-Newtonian fluid, depending on its molecular composition, ultimately leading to differences in flow through the opening at the end of the tube. Clinically and for the aesthetic community this means that HA fillers belong to the class of shear-thickening non-Newtonian fluids which increase their viscosity when subjected to stress like facial movements.

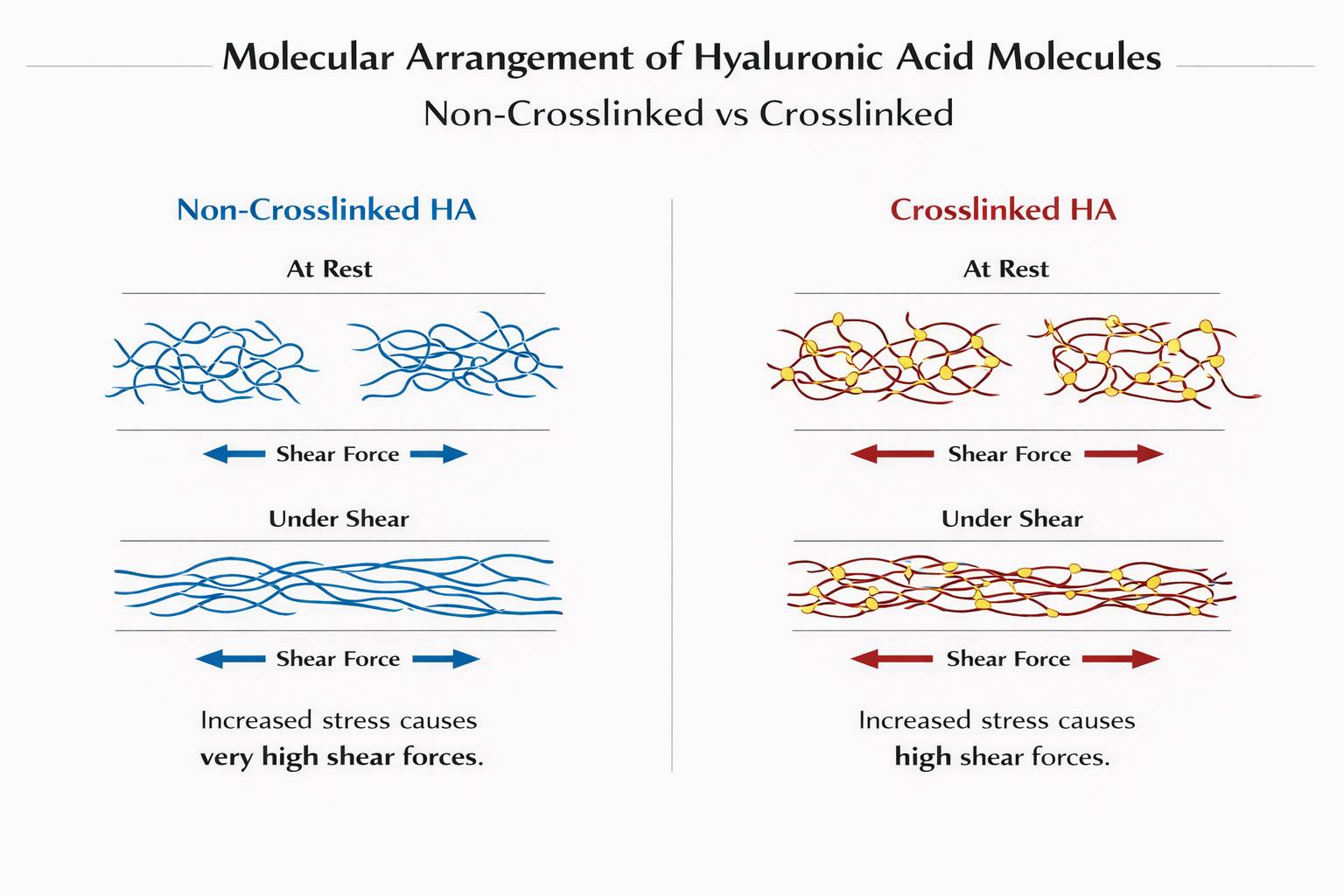

To investigate this aspect even further, a recent study investigated the differences between crosslinked and non-crosslinked HA fillers when subjected to different testing frequencies (0.1 versus 10 Hz). The results revealed that crosslinked HA fillers increased in their G-prime by 248% whereas non-crosslinked fillers increased in their G-prime by 3263%. This indicates that non-crosslinked fillers became statistically significantly harder under identical testing conditions when compared to crosslinked HA fillers. This change in G-prime can be understood if the analogy from the thought experiment is used: crosslinked HA fillers are like the elementary school kids on their way to the zoo, they hold hands, are aligned, walk the same speed, and stay in line. This allows the entire group to travel faster and be more coordinated. Whereas non-crosslinked fillers can be compared to the shoppers on Black Friday; the respective increase in shear forces is suddenly understandable.

The results of the above study mean clinically that non-crosslinked fillers can support the skin to withstand more shear forces during facial expressions and should be therefore injected superficially and in areas of high mobility like the periorbital or perioral facial regions. On the contrary, crosslinked fillers should be injected deep in areas where they can support but not block facial movements.

Of course, there are multiple nuances of the above and every treatment algorithm should be adjusted to the aesthetic needs of the patient. But knowledge of rheology can help to guide the treatment procedure and can help to understand better what is happening inside of syringes.

Read the full publication here: click PubMed

Join our community for news, offers, and updates on Cotofana Anatomy’s events and resources

Copyright © 2026, Cotofana Anatomy. All rights reserved.